Harnessing the Power of PCR for Accurate Disease Diagnosis

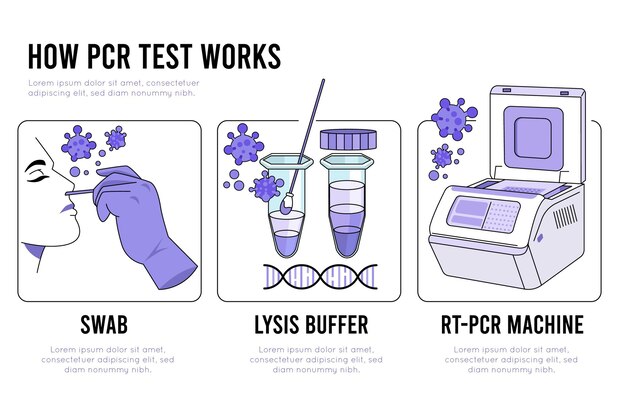

One of the fastest-growing techniques in modern medicine is using polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) to diagnose various diseases. This method is widely used to identify cancer, hereditary diseases, and some infectious diseases. It was first developed in 1983 by Dr. Kary Mullis, who later won a Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking work. Although the initial technology was quite basic, it has significantly evolved since then. Today, the primary reaction only requires a heat source, a sample container, and the right primers. However, the Information Age has brought about the development of numerous automated and electronic PCR machines.

PCR works by taking a small DNA sample and replicating it millions of times using thermal cycling and primers. This process triggers a chain reaction, causing the DNA to multiply rapidly; up to 40 thermal cycles can be used. PCR is also capable of analyzing very small amounts of DNA, making it valuable not only in medicine but also in forensics and archaeology.

The primers added to the PCR sample determine which section of the DNA gets amplified. One of PCR’s main uses is cancer diagnosis. For example, to diagnose leukemia, a technician mixes a patient’s DNA sample with a primer that will amplify the DNA of any leukemia cells present. If the DNA is detected, the patient has cancer; if not, they are cancer-free. PCR diagnosis is estimated to be at least 10,000 times more effective in early cancer detection compared to other current methods.

The same approach is used to diagnose hereditary diseases. The DNA primer targets the specific part of the genetic code linked to the suspected illness and amplifies it if present. In detecting viral and bacterial infections, technicians use a tissue sample from the patient and mix it with a primer that targets the viruses or bacteria suspected to be present. PCR is so sensitive that it can identify a viral infection even before the patient shows symptoms.

Advances in PCR technology are happening all the time, leading to numerous variations on the primary method, with more innovations being tested. One of the main challenges in expanding PCR’s use is developing the right primers. Currently, most diseases and conditions require specific primers. Researchers are working to create primers that can detect a wide range of issues, from different types of cancer to genes that predispose individuals to diabetes and other conditions.